Foraging, Knowledge, and the Everyday Technologies of Care: Walking with Mangalamma

At first light, Mangalamma sets out toward Hosakere, the pond near her village in Hunasanahalli. Her buffaloes walking along the way, around them, the edges of the path are thick with weeds, or what most people would call weeds. Mangalamma moves differently. Her eyes track the undergrowth, her fingers brush over the leaves, her pace slows where others would hurry. She slows with a kind of recognition. Honagone soppu (Alternanthera sessilis or sessile joyweed) for eyesight. Tonde soppu (leaves of the Ivy Gourd: Coccinia grandis) for khafa. Jaundice soppu, as the name suggests, to treat jaundice. She slows, reading the land.

Mangalamma, who works both as a Health Navigator and a member of the Manesiri Women’s Producer Company, foraging folds naturally into her day. The practice, learned from her mother as she accompanied her in the fields of Ramanagara from a young age, connects her work in food, health, and livelihood. As one of the women co-building the Channapatna Health Library, a digital repository of local health knowledge, Mangalamma’s daily movements through the landscape are also acts of documentation. What she picks, cooks, and shares eventually found its way into CHL’s growing collection of community health experiences.

The CHL began as a collective response as a way for women health navigators across Channapatna to record and share what they already knew about caring for themselves and others. It is now a living archive that connects food, medicine, local practices around reproductive health, and also the everyday life. While most of its contributors record experiences of pregnancy care, chronic illness management, or home remedies, Mangalamma’s foraging adds another dimension of knowledge to CHL that comes from walking, touching, tasting, and sensing as the repository is imaged to be growing.

The practice, as documented in the thesis project titled Tracing Stories Through Soppus by Ananya Sarangi (Srishti Manipal Institute & Living Labs Network, 2025), is as much about attention as it is about plants. Ananya’s work with Mangalamma describes how she identifies edible greens as a sight, as a texture, as a sound, the rasp of tonde soppu’s “hairy leaf when crushed,” the “softness” of Pasarai soppu underfoot, the “strong, distinct smell” of Ganake soppu (Garden nightshade, scientifically called Solanum nigrum). Watching her, Ananya noted, is to see technology in another form, that is as an embodied technique, refined through repetition and sustained by memory.

Greens foraged and being cleaned as captured by Ananya

This technology as against machines and apps here is a system of gestures, habits, and checks that ensure continuity. When Mangalamma pinches a stem just above the leaf node, leaving the base intact for regrowth, it is care and calibration at the same time. This idea of sustainability is learned over years of practice. Her way of foraging is a way of regeneration which is precise, local, while also being responsive. Within the CHL’s broader work, such methods are recorded as they offer a fresh narrative to the idea of health knowledge. In the repository, such knowledge circulates through the daily rhythms of life. Mangalamma’s foraging shows that understanding health requires paying attention to how people also sense what is edible, safe, or healing.

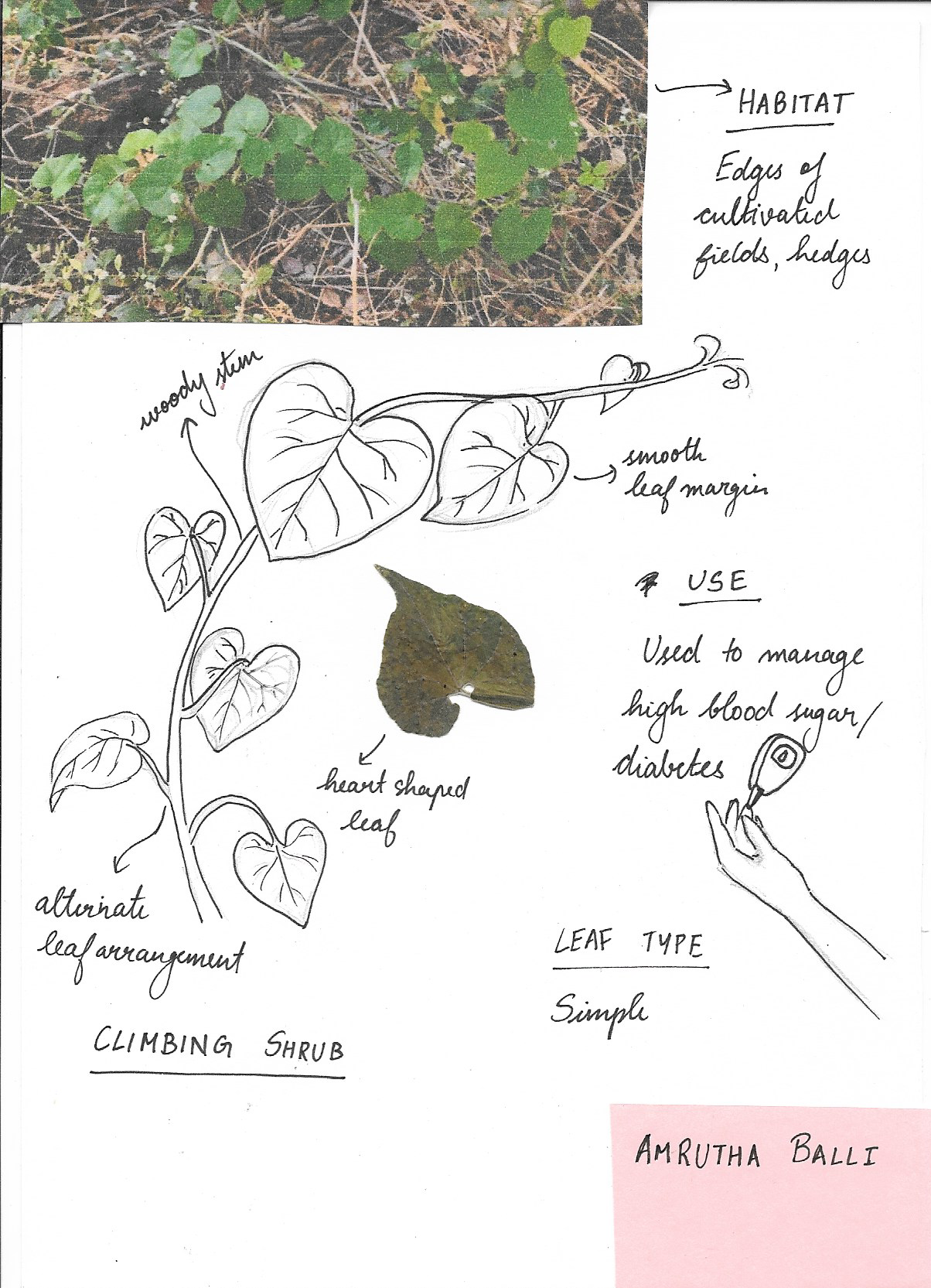

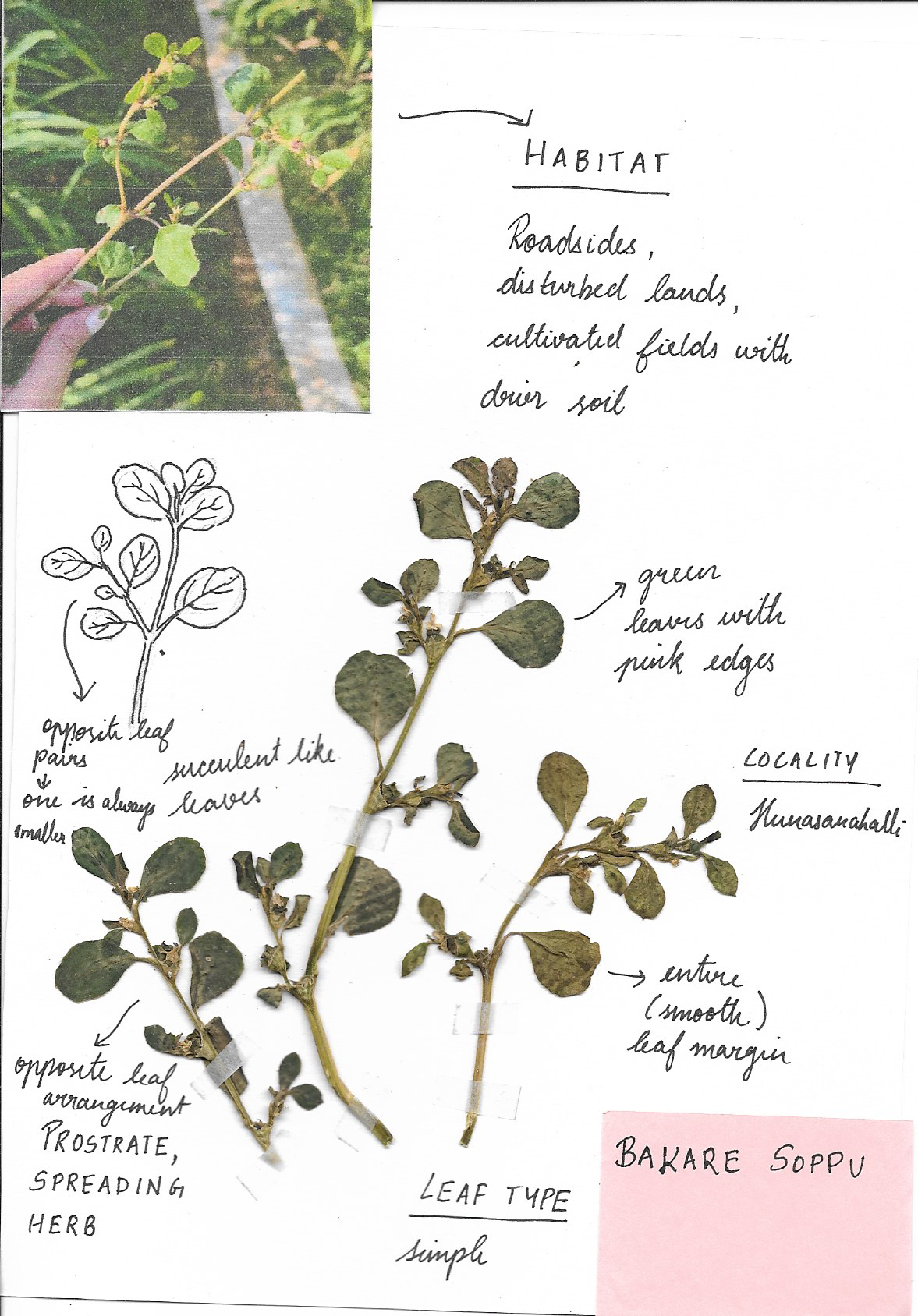

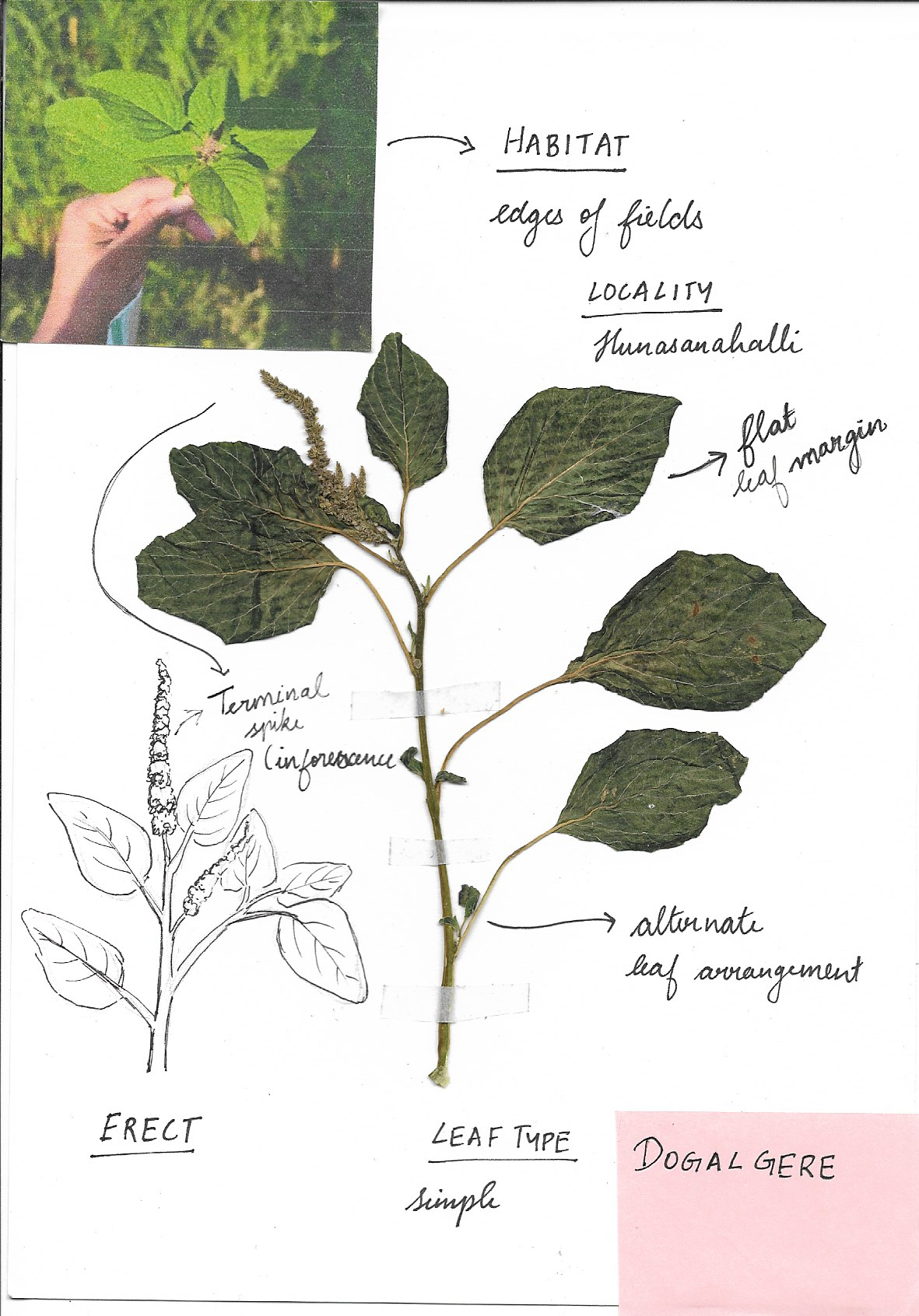

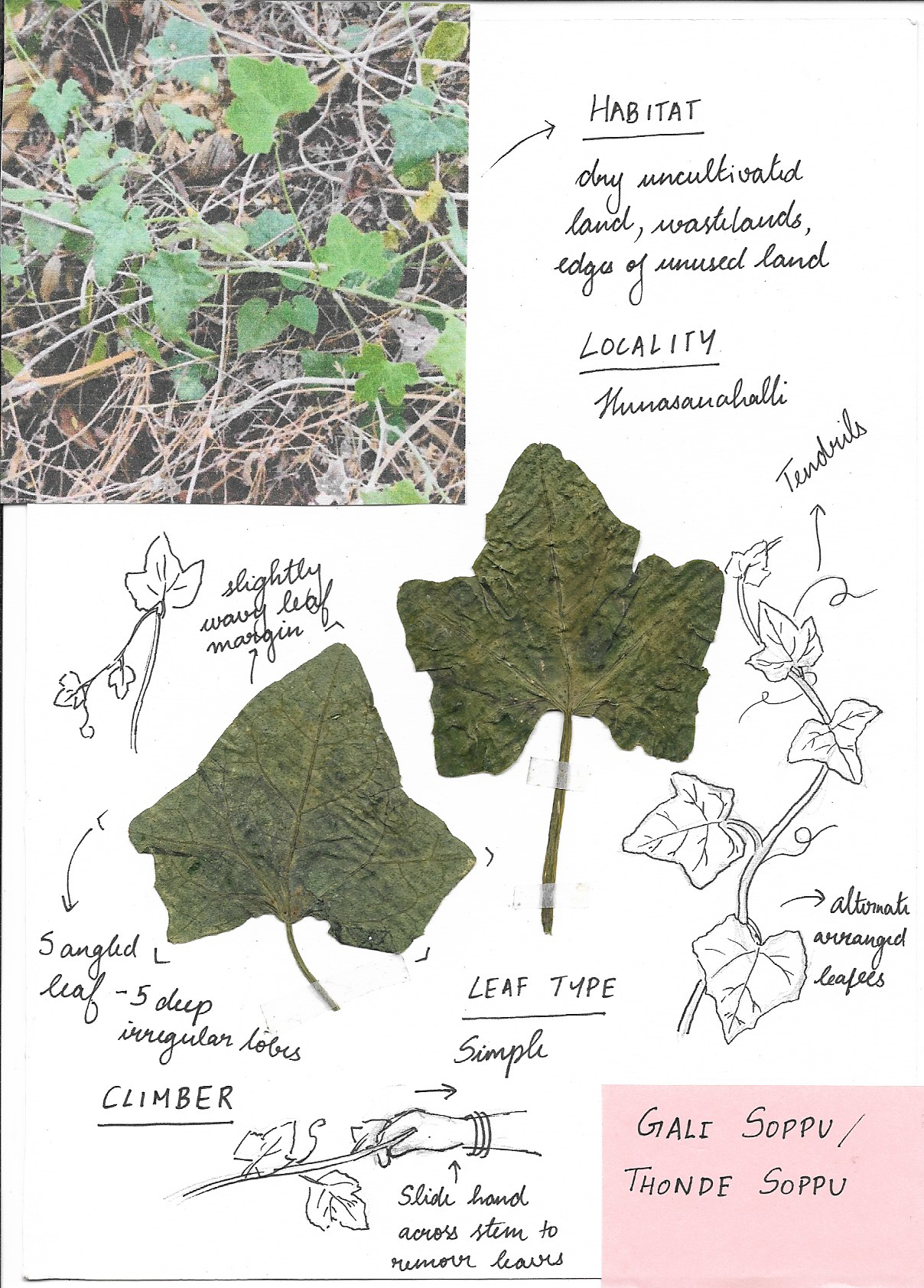

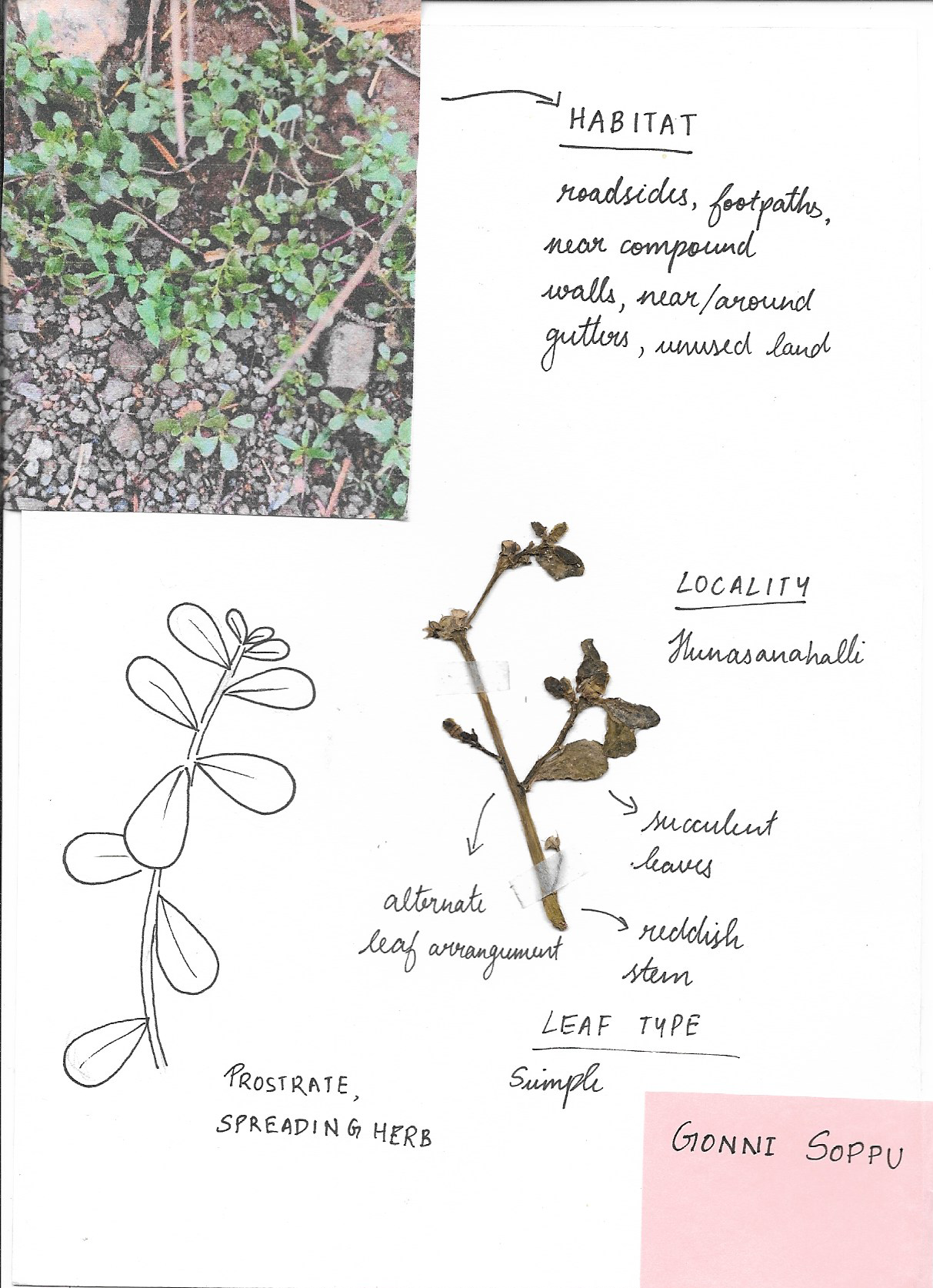

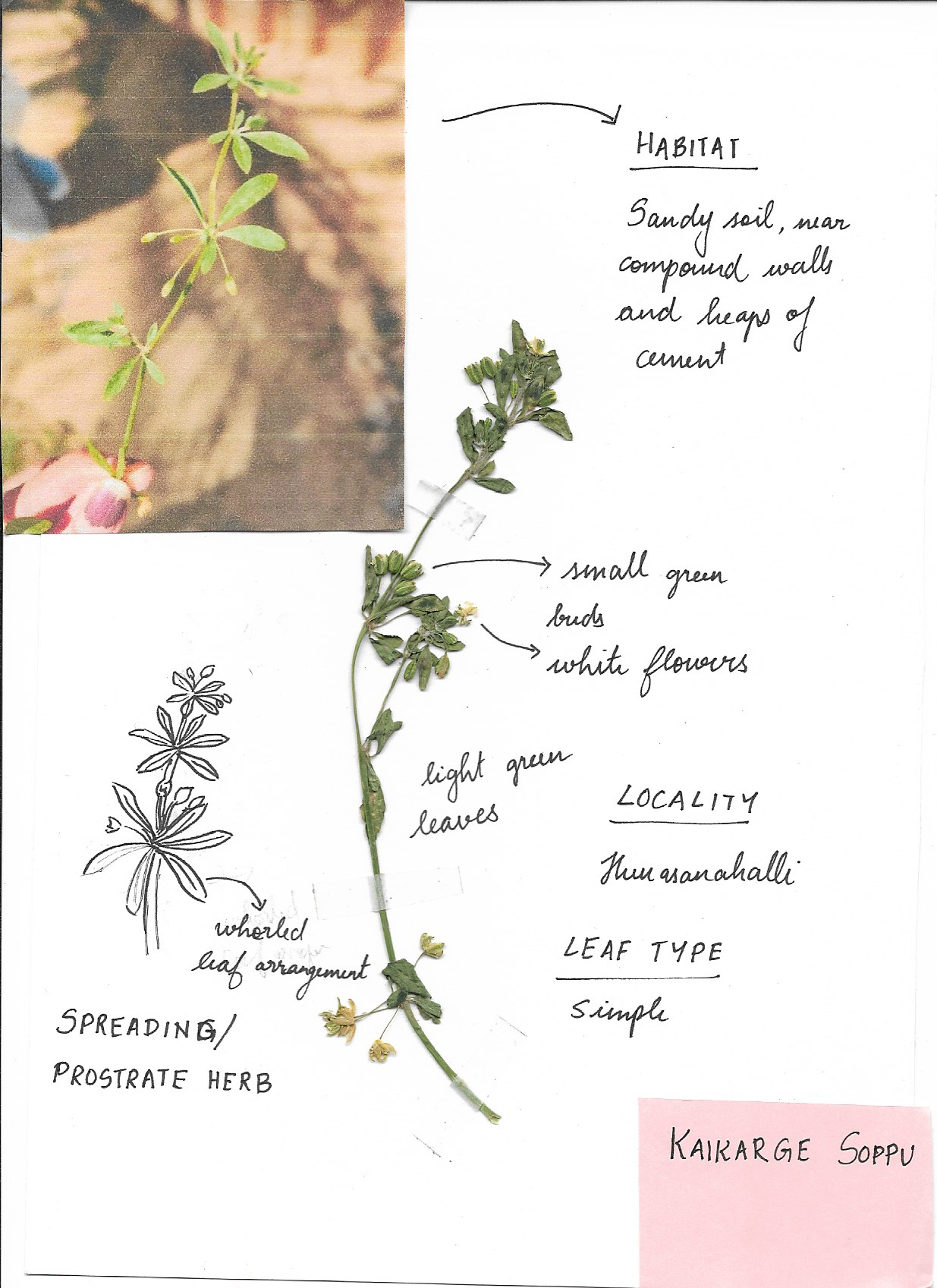

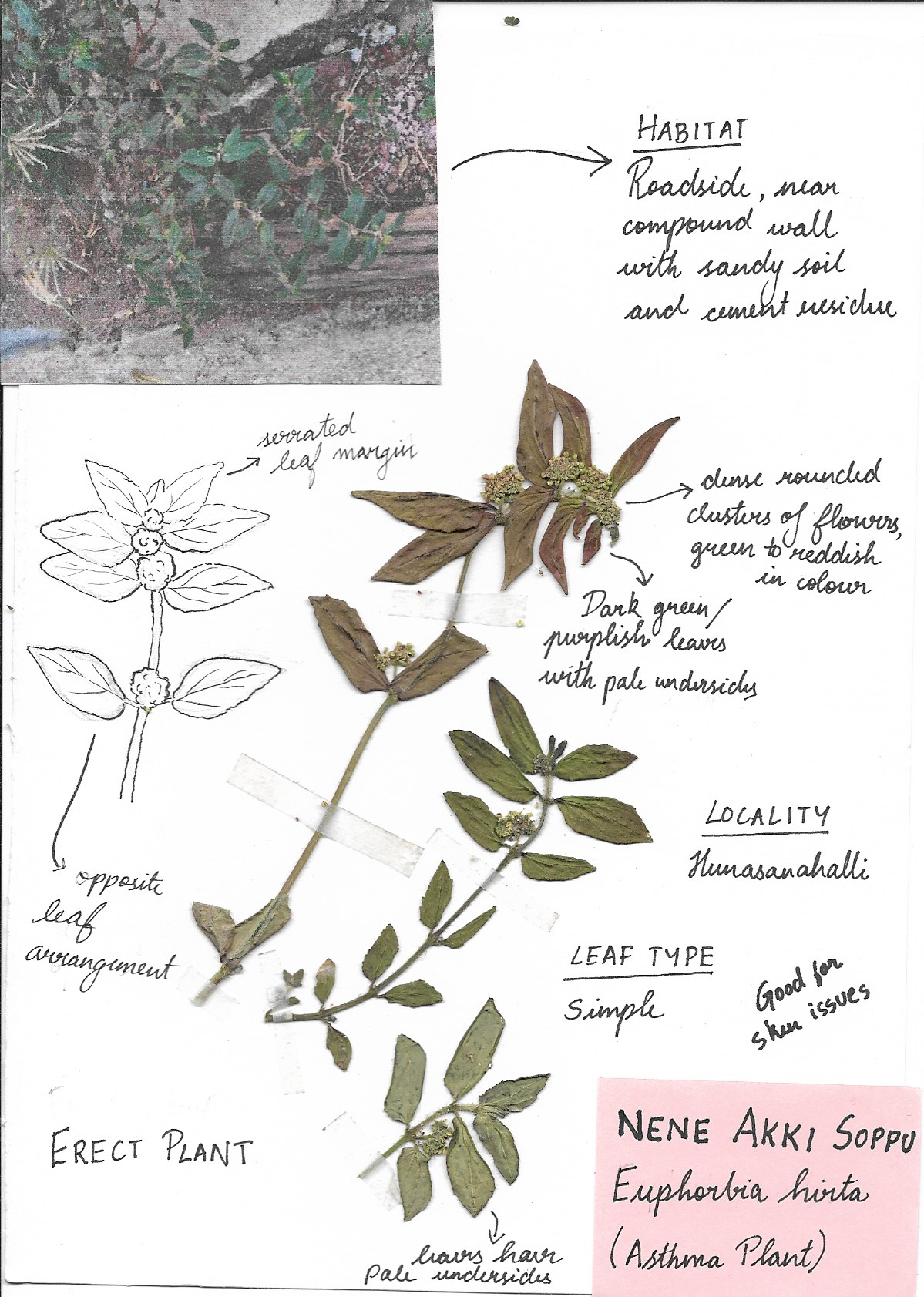

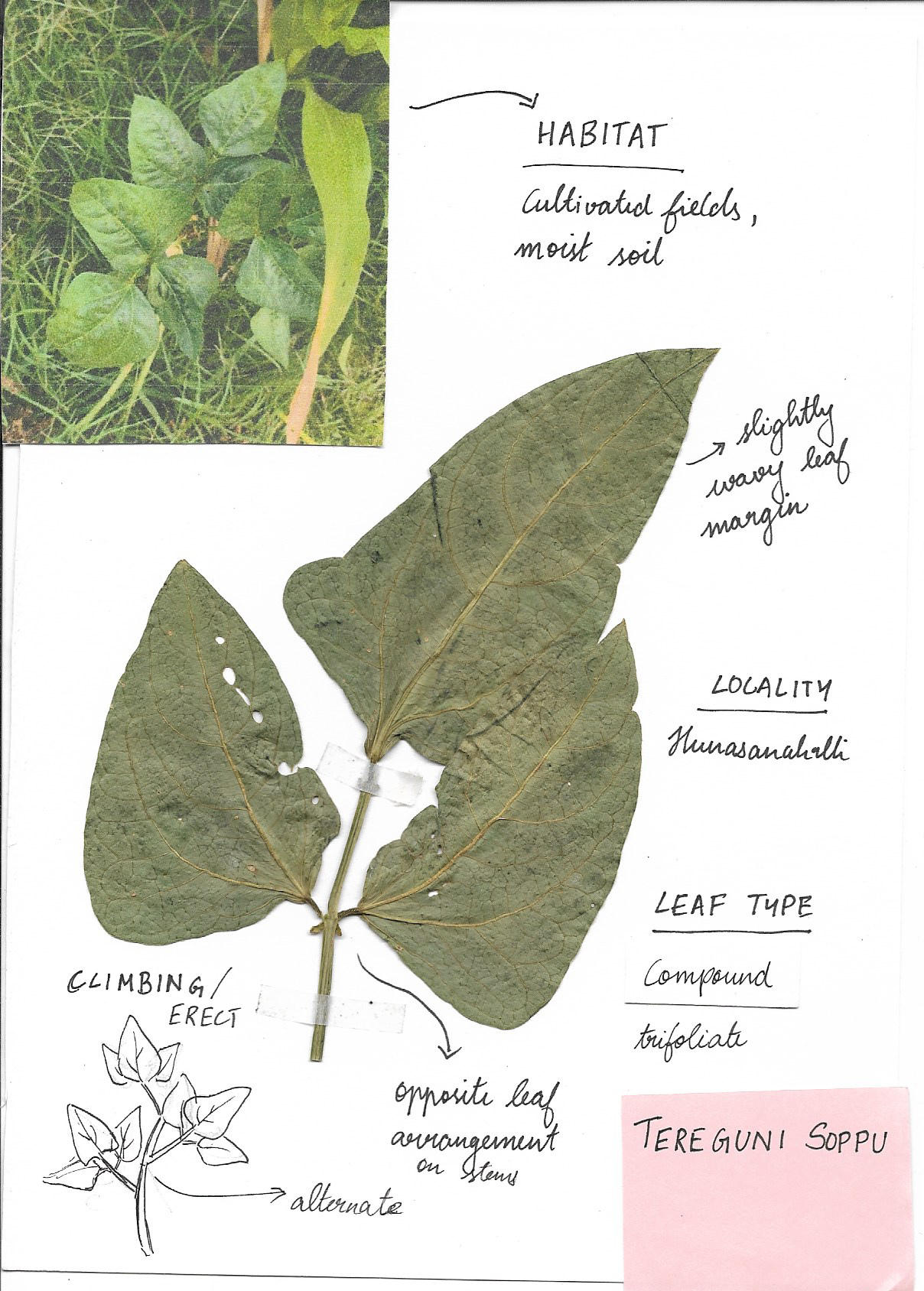

Ananya’s documentation goes further, turning this embodied knowledge into shareable form. She and Mangalamma co-created herbarium cards with pressed leaves annotated with the plant’s local name, habitat, and use.

Herbarium cards, with annotations by Ananya Sarangi, in conversation with Mangalamma.

This conversation is at the heart of what the CHL attempts to build a repository that is participatory. In a sense, the herbarium and the digital library belong to the same ecosystem. While one preserves leaves and stories, the other preserves the conditions in which these stories can be remembered and told again. How do we co-imagine this embodied practice becoming an artefact to learn from? Can the smell of Ganake soppu or the weight of damp soil be translated into digital form without losing meaning? These are questions that CHL continues to work through, by documenting and archiving practices actively while local knowledge circulates beyond the household, across places, into the communities.

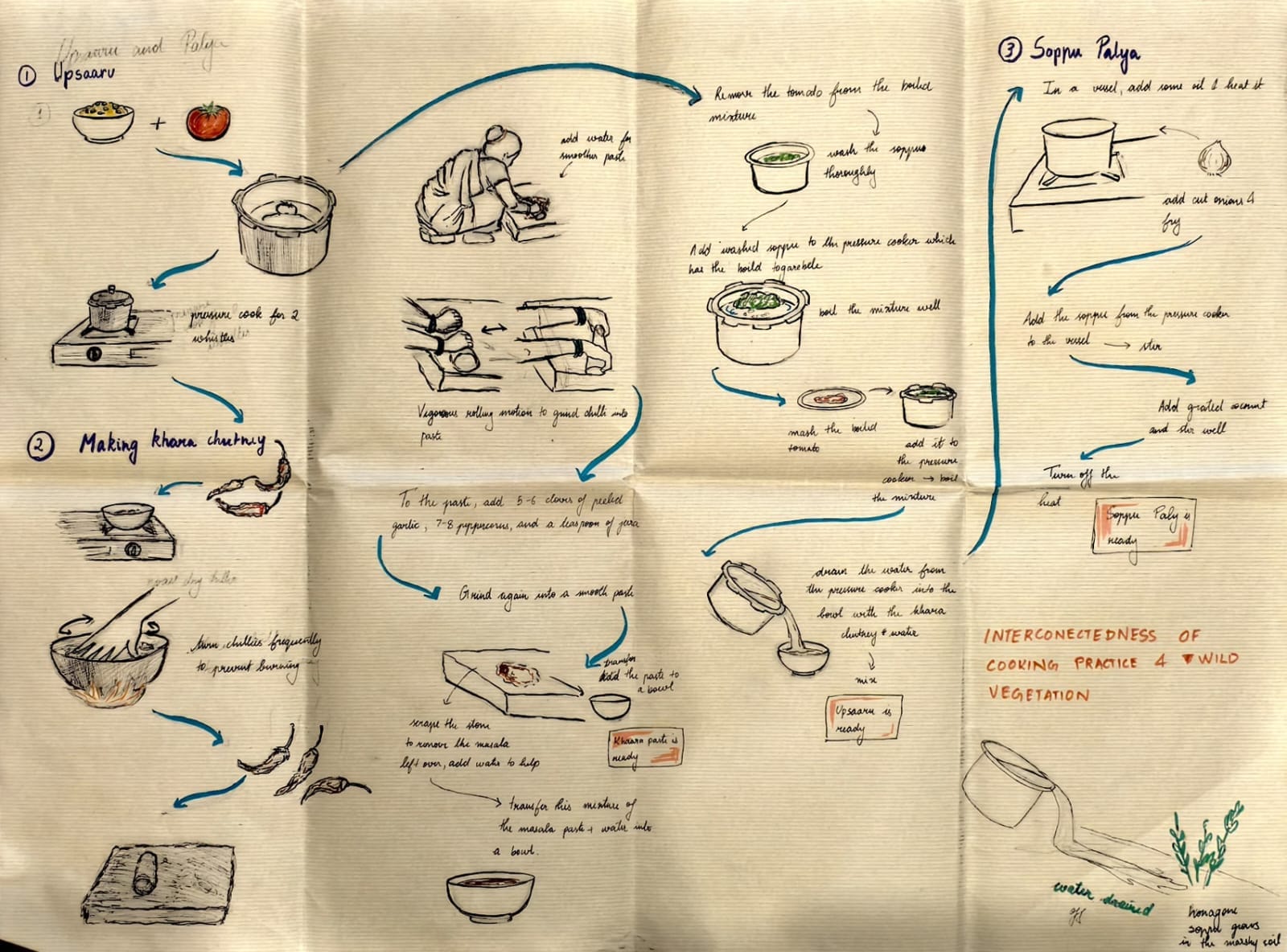

For Mangalamma, everyday foraging further links to cooking, to the taste of soppu palya, the boiling of upsaaru, the steady pulse of ponding spice on the amikallu. Nothing gets wasted, the water used to rinse grains becomes kalgacha, feed for her buffaloes. The runoff outside her kitchen seeps into the earth, creating a small marsh where Honagone soppu grows thick. Her kitchen and her field both are connected loops, each feeding the other. Through such loops, CHL finds its form as a collection and a network of practices that hold the idea of health and care together. The work is rooted in memory, trust, and the everyday acts of women health navigators. Because knowledge sometimes grows sideways, like Pasarai soppu, spreading across the ground quietly, holding the soil and stories together.

Foraging in Channapatna extends far beyond Mangalamma’s practice. As documented by Ananya, each household and community engages with soppus differently. Mangalamma’s daily foraging for food and Mane maddu, Sarasamma’s soppus for animal feed, as she primarily forages soppus to feed her goats and cows, sits in a different but related register.

Sarasamma’s work in Dyavapatna is shaped by a long familiarity with animals, one she traces back to her childhood on her parents’ farm. “Today she raises cows, goats, and sheep in the fields behind her home, moving through their routines with a kind of practiced attentiveness, feeding, checking, and observing them through small daily cues,” as recorded by Ashritha Lolugu, (Srishti Manipal Institute & Living Labs Network, 2025) in her thesis project Hands that care. She identifies each animal through their gait, their horns, the way their eyes look when they’re hungry or unwell. Her knowledge is built almost entirely through lived experience, sharpened by memory and the unspoken rhythms between her and her animals.

The animals also respond to her presence before she even reaches the shed, a low call, a shift in posture, and she replies to them with nicknames and mimicry, reading their moods easily. When a young sheep struggles to feed, she prepares milk in a bottle; when a cow shows signs of fever, she recalls recipes passed down from women in her neighbourhood. Care emerges in these decisions; which fodder to give a pregnant goat, how long to keep a cow in the shade during summer, when a homemade remedy is enough and when a veterinary visit is necessary. The practice of foraging becomes an extension of her care.

Hakims like Sharif and Maqsood source herbs for Unani treatments. Gayathri Rajiv’s (Srishti Manipal Institute & Living Labs Network, 2025) fieldwork as part of her thesis project, adds another angle to how foraged and locally sourced materials shape health practices in Channapatna. Her observations show that Hakims rely on trusted suppliers and also on the ecological knowledge embedded in local landscapes. Sharif, for instance, sources his bhasma ingredients from Mysore, Bangalore, and Baba Budangiri, supplementing them with materials gathered at village jatras, where traders and foragers make seasonal herbs available. His practice blends the mineral and vegetal, the metallic nature of Loha Bhasma toasted longer to shift its colouring from black to red to enhance its benefits, with herbs gathered through networks of traders and local foragers. Maqsood sir, meanwhile sees foraging as a spiritual dialogue. He remembers, as Ananya writes, “how his grandfather could hear herbs, “speak to him… mere se dawa banao,” when a patient arrived. His practice now involves sourcing from Mysore and Nanjangudu, he still also travels to the forests to collect specific herbs, also mentions how, “with rapid construction and fewer green spaces, they have become harder to find.”

Learning about the practice of bone setting

The pashu sakhis of Kodamballi prepare nati aushadi for cattle, blending bevu soppu, nugge soppu, unchi soppu, and bella into healing mixtures that “cleanse the body after calving or treat weakness in cattle.” These interconnected practices show how foraging links human, animal, and ecological care.

An interactive map by Ananya tracing the herbs, recipes, remedies, and where Mangalamma forages, across Kodambahalli, Kondapura, Bangahalli, Nagapura, Madapura, Hanchipura, and her own village, Hunsanahalli can be viewed here. To explore additional related documentation on local soppus, see Uncultivated Greens documented by Abhishek.

Plants, Foods, and Ingredients

Honagone soppu – Sessile Joyweed / Alternanthera sessilis; edible green used for eyesight.

Tonde soppu – Leaves of Ivy Gourd (Coccinia grandis); used for treating khafa.

Jaundice soppu – Local green used in jaundice remedies.

Pasarai / Pasari soppu – A soft-textured edible green.

Ganake soppu – Garden nightshade (Solanum nigrum).

Mane maddu – Household remedies.Soppu / Soppus – Greens, leafy plants.

Upsaaru – A watery broth made by boiling greens/vegetables.

Soppu palya – A sauteed greens dish.

Kalgacha – Water used to rinse grains, later used as cattle feed.

Bevu soppu – Neem leaves.

Nugge soppu – Drumstick leaves.

Unchi soppu – Local herbal green used in cattle medicine.

Bella – Jaggery.

Medical, Healing Terms

Khafa – Phlegm.

Bhasma – Calcined ash used in Unani medicine.

Loha Bhasma – Iron ash used medicinally.

Nati aushadi – Local/native medicine.

Pashu sakhis – Trained community-based animal health workers.

Other terms

Amikallu – Traditional grinding stone (mortar).

Hakim – A practitioner of Unani medicine.