More-than-human Networks of Hara

Networks are all around us. When we closely examine the veins of a leaf or take a bird’s-eye view of modern cities, networks reveal themselves as embedded in the living ecologies we inhabit. I have a deep fascination with, and a growing interest in, learning to see networks beyond the confines of wires, cables, antennas, and routers.

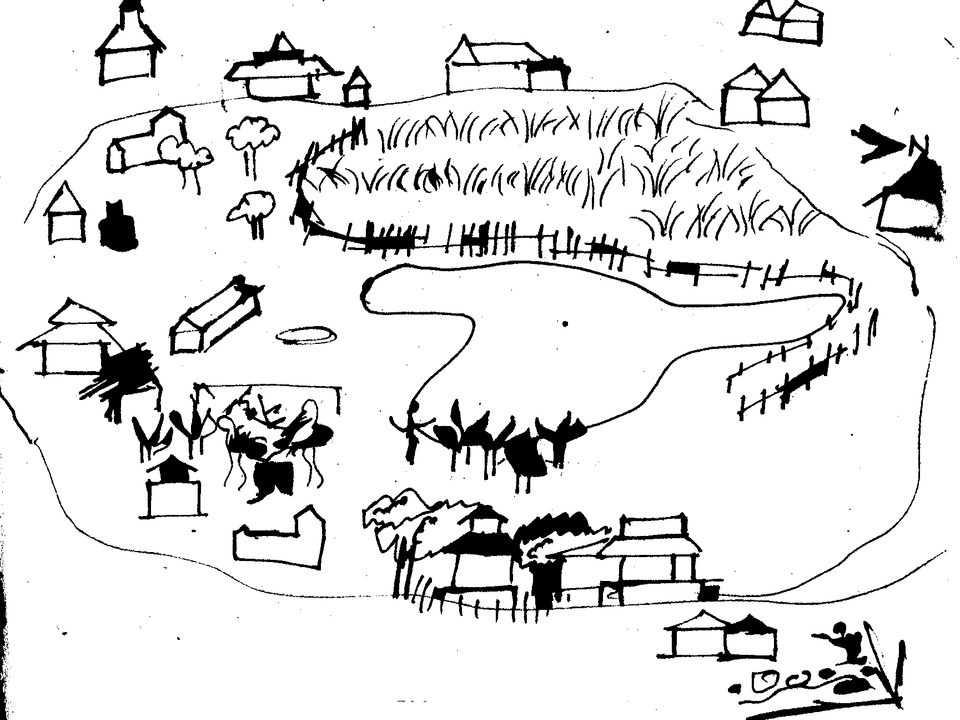

In the hamlet of Hara, nestled in the forests of coastal Karnataka, networks stretch far beyond human-made infrastructures. They are rooted in the soil, distributed by the water, woven through the trees, and echoed in the barks of dogs. These are networks not engineered by machines but grown through relationships, embedded in the more-than-human ecologies of place.

Networks of the unconnected

Samagra Arogya is a long-term, place-based engagement aimed at understanding and responding to the social determinants of health within a cluster of seven gram panchayats in Kundapura taluk. Within this initiative, one of our current engagements focuses on co-building situated infrastructures like community mesh networks that are responsive to local needs and realities. In remote tribal hamlets like Hara, with around 20 households, the needs of the community are often overlooked by both the state and corporations. As a result, access to Hara is limited—there are few roads and no reliable telecommunications.

While we work with the people of Hara to imagine a local mesh network, being in the place is a humbling reminder that Hara already has its own networks. These networks are not made of routers and cables but of the bonds between people, animals, and landscapes. Modern, Eurocentric imaginations of technology, driven by universality and utilitarianism, often obscure these relational ways of being. Yet, Hara’s networks inspire us to think beyond these rigid definitions and towards more situated and relational understandings of connectivity.

Watchdogs Security Network

Our earliest visits to Hara were marked by dogs chasing us away. As we moved around the hamlet, dogs would guard the premises of homes, alerting their owners to our presence. At first, this seemed like a natural response to outsiders, but over time, we learned of a deeper context. The hamlet had recently experienced cases of theft, prompting each household to keep at least one dog as a safeguard. We were told that if we had visited a couple of weeks earlier, nobody in the community would have even spoken to us out of suspicion. Dogs are very much an integral part of Hara’s ecosystem of security.

Dogs have long been a part of more-than-human networks across geographies. They have keen sensory abilities. Their heightened sense of smell, acute hearing, and sensitivity to movement make them exceptional at detecting changes in their environment. And they need no electricity or programming for sensing. Their sense of territoriality furthers this argument even more. They instinctively patrol and protect spaces they recognize as their own. This is perhaps far more agile than seven CCTV cameras. Beyond individual households, dogs also interact with each other, forming their own social networks that enable collaborative responses to threats. In Hara, dogs from nearby houses were often seen playing together. They also guard the premises collaboratively - the moment one of them detects an outsider and barks, the signal is broadcasted to neighbour dogs triggering a chain reaction of bark alarms.

What makes dogs particularly unique is their social intelligence. Their ability to read human cues, interpret emotions, and respond accordingly fosters a relational bond that transcends mere utility. To go back to our first day in Hara, there was but one young pup that saw us strangers with kindness. He accompanied us as we went around the hamlet, often leading the way for us. This animal-human relationship is an example of what Donna Haraway calls becomings-with: an ongoing, co-constitutive process through which humans and nonhumans shape each other’s lives. In Hara, these dynamics have organically evolved in relational, adaptive, and deeply situated ways.

Living Archives of Relational Pasts

Beyond the bonds with dogs, the community’s histories and practices, such as their reverence for the daivas like Panjurli, illustrate a profound interconnectedness with animals. These traditions remind us that the community’s ways of knowing and being are deeply ecological and rooted in relational lifeworlds. The daivas, often seen as guardians of the land and its people, embody more-than-human agencies that shape the moral and ecological fabric of Hara. Stories of Panjurli, a boar spirit, not only highlight the spiritual significance of animals but also reflect the community’s relationality to the forest and its many life forms.

These histories are living archives of ties between the community and their environment in ways that transcend utility or ownership. While learning of such practices, we are reminded that more-than-human networks like these are not remnants of a bygone era but active, dynamic systems of knowledge that continue to inform life in Hara. They challenge us to see connectivity not just in terms of infrastructure but as an ongoing dialogue between the human and the more-than-human. These networks hold the potential to inspire alternative visions of belonging, rooted in the specificities of place and history, while resisting the homogenizing tendencies of state and corporate agendas.

In Hara, what we have learned so far is that networks aren’t something you install but something to listen to, to look closely at, and to learn from. They are already present in the stories told by its people, animals, and landscapes—woven through histories, relationships, and ways of being that are deeply attuned to place. As we work with the community of Hara, we are not only building infrastructure with the community but also learning ways to reimagine the very idea of connection itself.