Grama Drishti Fellowship for Samagra Arogya

A place based learning initiative

Context & Design

The Grama Drishti Fellowship is a place-based learning initiative designed for youth and adolescents from seven Gram Panchayats under the Samagra Arogya initiative in Kundapura Taluk, Karnataka. The fellowship provides a platform for young individuals to explore the Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) through collaborative, community-driven engagements. It aimed to develop local leadership by equipping fellows with skills to analyze and address health and well-being concerns through participatory learning methods. Fellows engage with local mentors in the 7 GPs, governance structures, and technological tools to co-create knowledge and interventions. It responds to a locally grounded question: how might young people engage with everyday knowledge systems and community well-being through sustained and situated inquiry?

By fostering co-learning, creative experimentation, and community participation, the fellowship enables young people to think and work on sustainable practices that are locally relevant. The program includes interactive workshops, structured learning modules, and hands-on practicum experiences that enable fellows to collaboratively contribute to local governance and well-being initiatives actively.

Initially envisioned as a fellowship for youth between the ages of 18-24 to explore the SDoH, the program went through several iterations. The original design included modules on local governance, oral histories, digital tools, and local advocacy, with a focus on participatory governance and localized understand of health and well-being. The intent was to co-develop learning journeys with local mentors, supporting youth in drawing connections between lived realities and systemic patterns.

However, through the recruitment phase, we learned that this age group had largely migrated for work or education. This insight required us to return to the place and revise our approach. Based on our field observations and conversations, we re-imagined the fellowship for adolescents aged 10-17 and co-designed it with seven active local mentors.

The reframed fellowship focused on exploring local knowledge systems, stories, foods, plants, and village histories, all rooted in specific contexts of the seven GPs: Hemmadi, Hakladi, Keradi, Chittur, Vandse, Idur Kunjadi, and Aloor. The emphasis remains on observation, documentation, and sharing, rather than training or predefined outcomes.

Process

Local mentors, self help groups and governance interactions: recruitment

We aimed to build a strong network of local mentors who could support and guide youth fellows in their place-based learning journeys. Recognizing the importance of community-rooted knowledge, we engaged with experienced people who could provide mentorship and facilitate deeper community connections. This process has strengthened trust among our collaborators, expanding our networks and opportunities.

Orientation introduced fellows to Samagra Arogya’s principles through immersion activities, governance interactions, and participatory research exposure. Learning modules included primers on Social Determinants of Health (SDoH), governance, and place-based learning, along with electives in digital mapping, oral history, and advocacy tools, complemented by peer-based discussions and study circles. During the practicum phase, the fellows would explore specific micro-contexts, collaborating with mentors and communities to document lived experiences and create public knowledge artifacts. The program was designed to end with peer reviews, a collective synthesis of findings into a Place-Based Glossary of SDoH, and a public exhibition to engage local governance and wider audiences.

We met all of collaborators on field to onboard them as mentors which was followed by co-deisgn session with 7 active mentors. They contributed to the idea of the fellowship and shared their suggestions.

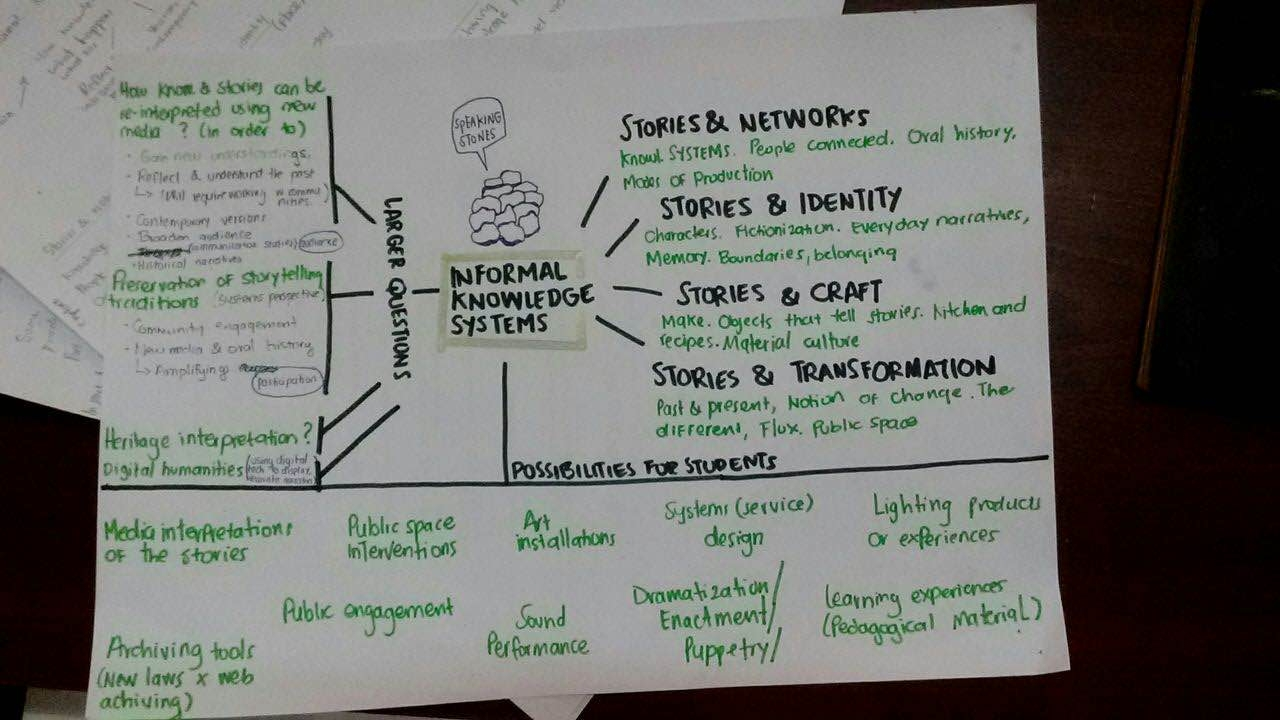

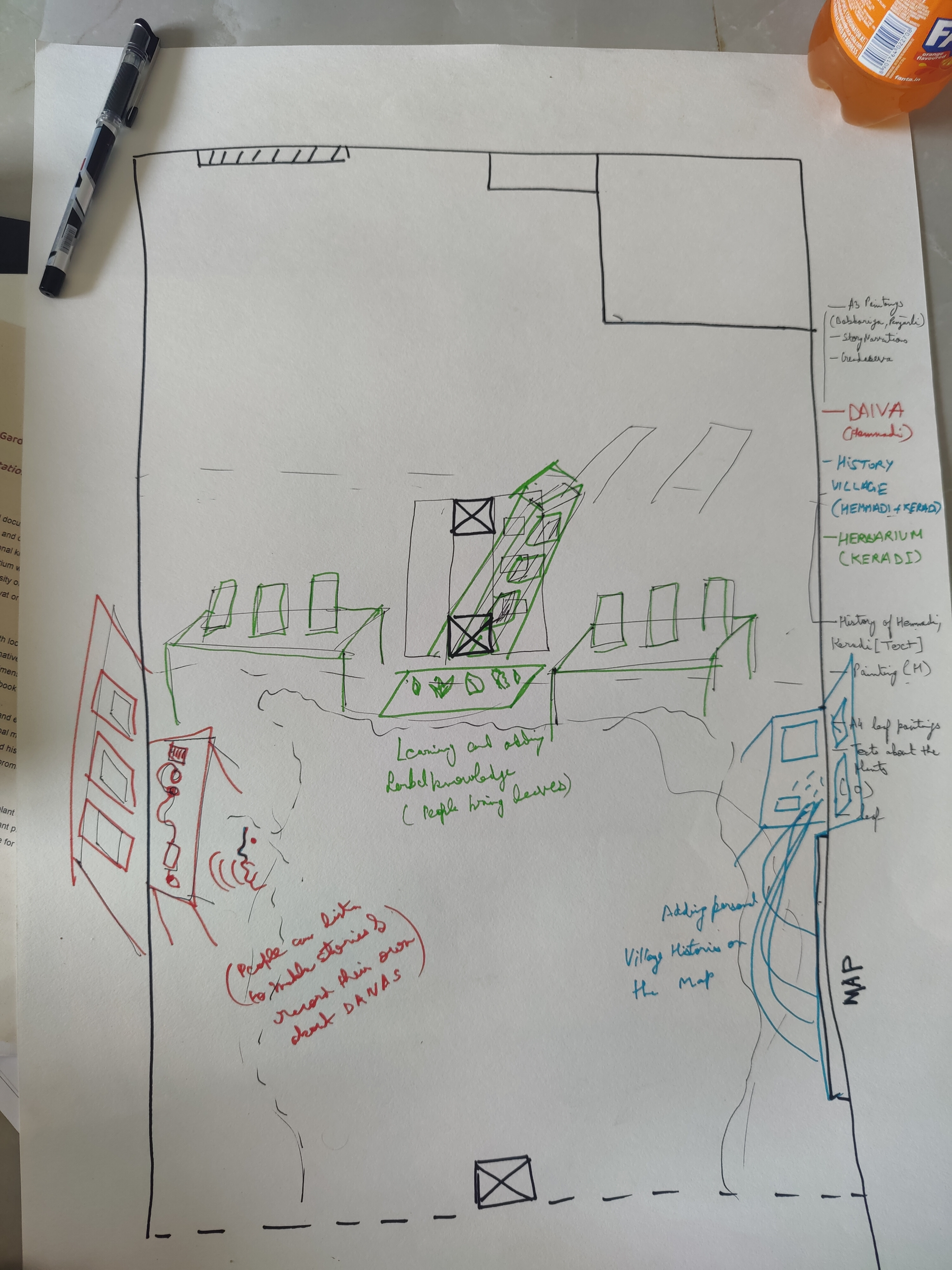

Reframing our approach and defining modules

We started our work with them by January. There were many ideas which emerged in the co-design session with the 7 local mentors. The ideas which were contributed by them were fleshed out in January. These perspectives shaped the new directions of the fellowship, helping define themes such as:

- Herbal Garden, Herbarium

- Daiva Stories

- History of the name of the village

- Karavali Recipes

The Grama Drishti Adolescent Fellowship engages children in documenting and showcasing informal and traditional knowledge systems in seven Grama Panchayats of Kundapura Taluk: Hemmadi, Hakladi, Keradi, Chittur, Vandse, Idur Kunjadi, and Aloor. The fellows, aged 10 - 17, will work on projects focused on oral histories, food traditions, biodiversity mapping, and village history. These projects are designed to capture lived experiences and preserve cultural heritage through various mediums such as writing, illustrations, and recordings. Local mentors and the Samagra Arogya team will guide the fellows in executing their projects. Each project will follow a structured timeline, ensuring well-documented outcomes in the form of books, digital archives, or exhibitions.

Starting the fellowship

To support the fellows in their documentation and research, we provided a Fellowship Kit containing essential materials such as:

- A notebook to be maintained as daily journal, notes and sketch

- Print out of their project brief and plan

- 300 GSM Watercolour paper

- Pen, pencils, sharpener and eraser

- Water Colours

- Crayons

- Sticky notes

- Two Chart papers

- Fevistick

Two Approaches to Working with Fellows

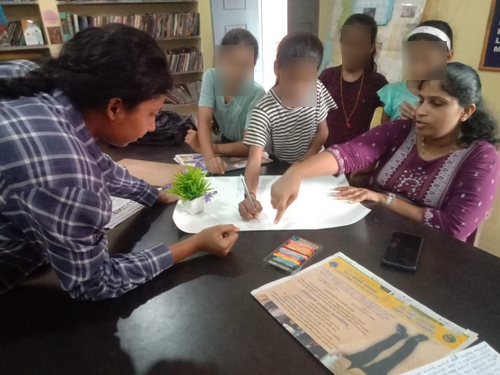

At the Hemmadi Library

In Hemmadi, adolescent children regularly use the local library to study and spend time together, making it an ideal space for their fellowship projects. So we provided a common fellowship kit which had a pair of all the stationery listed above as they worked as groups

Here, they could access resources, collaborate, and receive mentorship from Suresh. Harsha and Harshita, introduced by Geetha, had the flexibility to either work from the library or complete their projects at home with guidance from their mother and Shruthi. We distributed one fellowship kit each to them.

At a home in Keradi

In Keradi, Anuja’s home served as a community workspace, offering a safe and accessible environment for fellows to work together. First we met Nidhita and gave her the kit. Chaaya was a little far away from Nidhita’s house. So we went to Bellala and met Chaaya and here family while distributing the kit. This flexible approach allowed participants to engage without travel constraints, ensuring meaningful participation in the fellowship.

Since many fellows were adolescents, obtaining parental consent was a crucial step in ensuring their active participation. We engaged with families to explain Samagra Arogya by showing our work physically. Often times when we were in Keradi, the family also got involved to give suggestions and information.

Pic 1 working in Keradi and Pic 2 at the Hemmadi Library

The Fellowship kicks off!

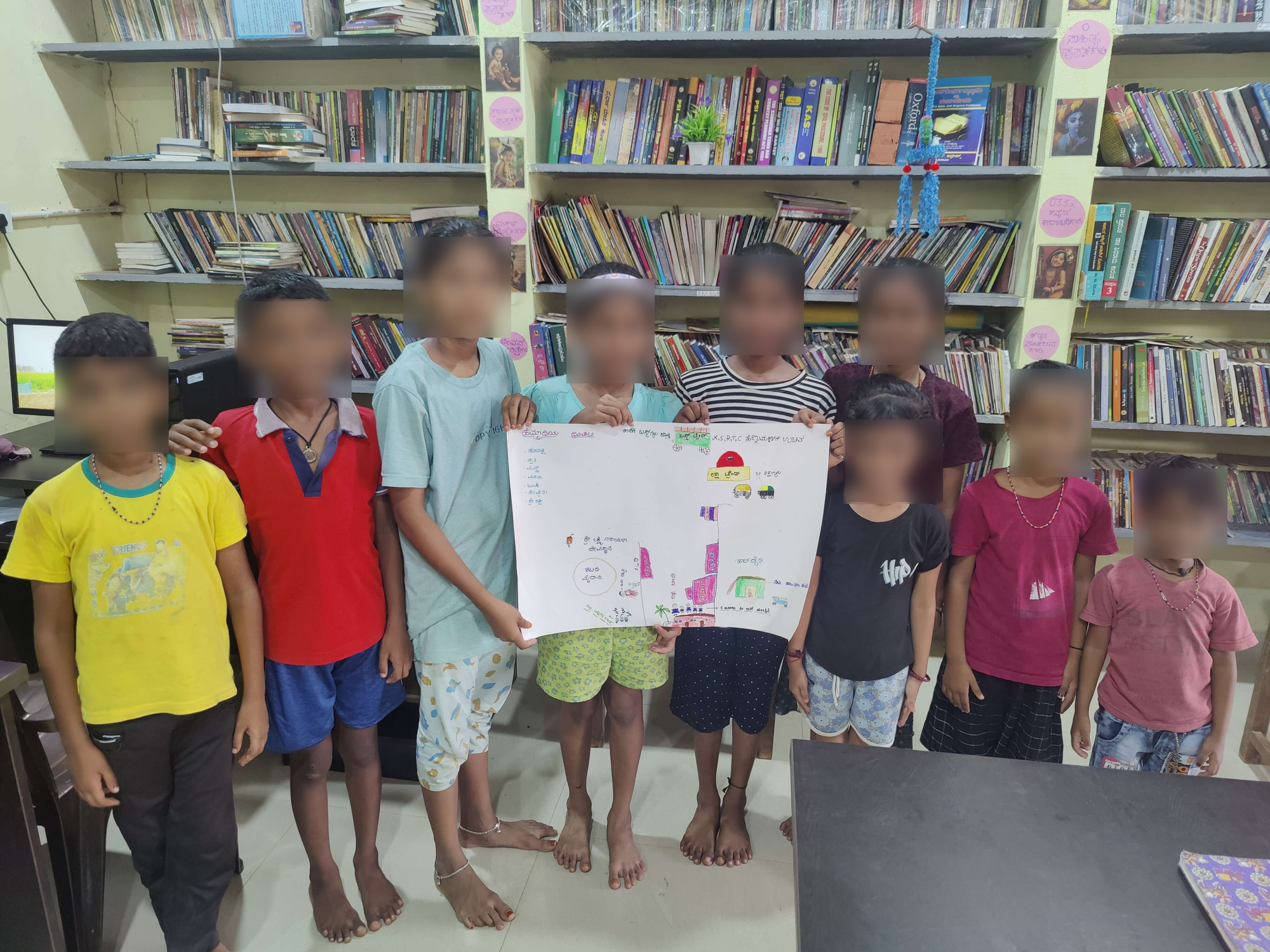

From February fellows engaged in various activities that combined storytelling, documentation, and mapping. Story reading sessions introduced them to Kannada folklore and cultural narratives, sparking discussions on language differences between spoken Kundapura Kannada and written Kannada.

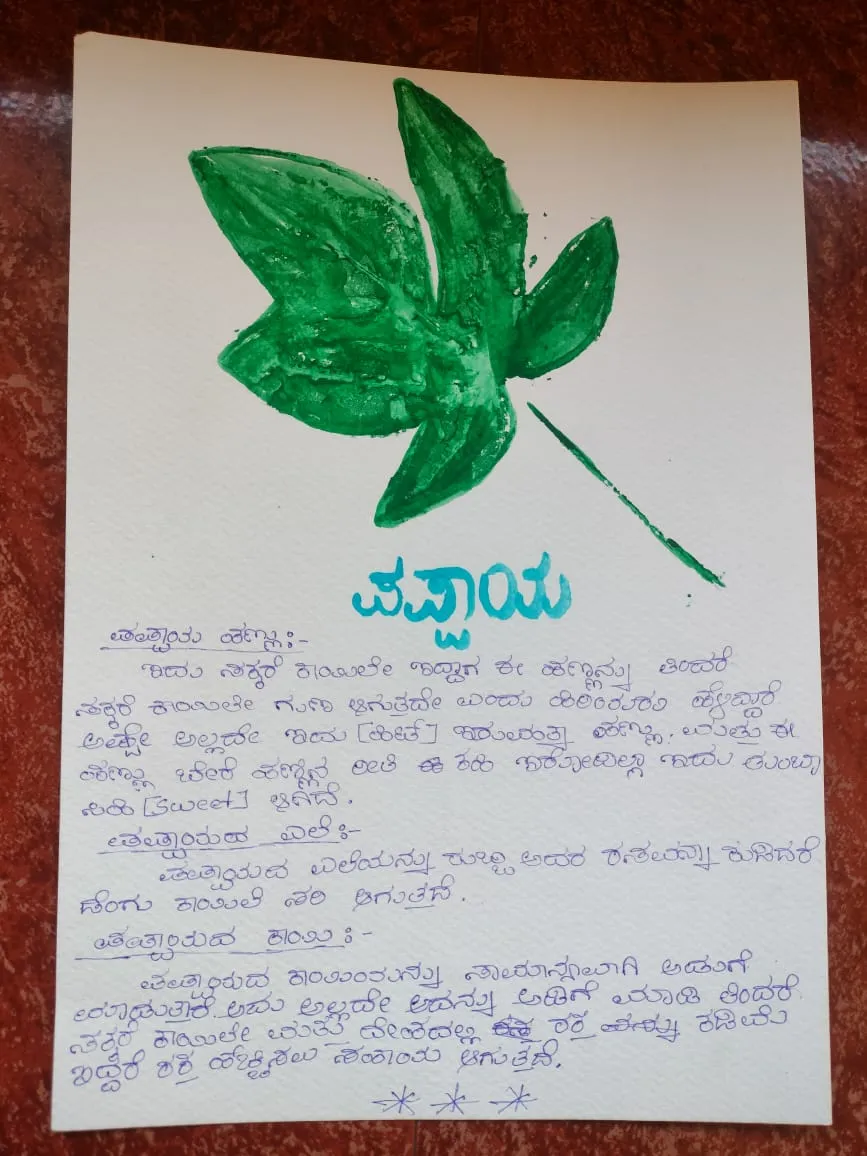

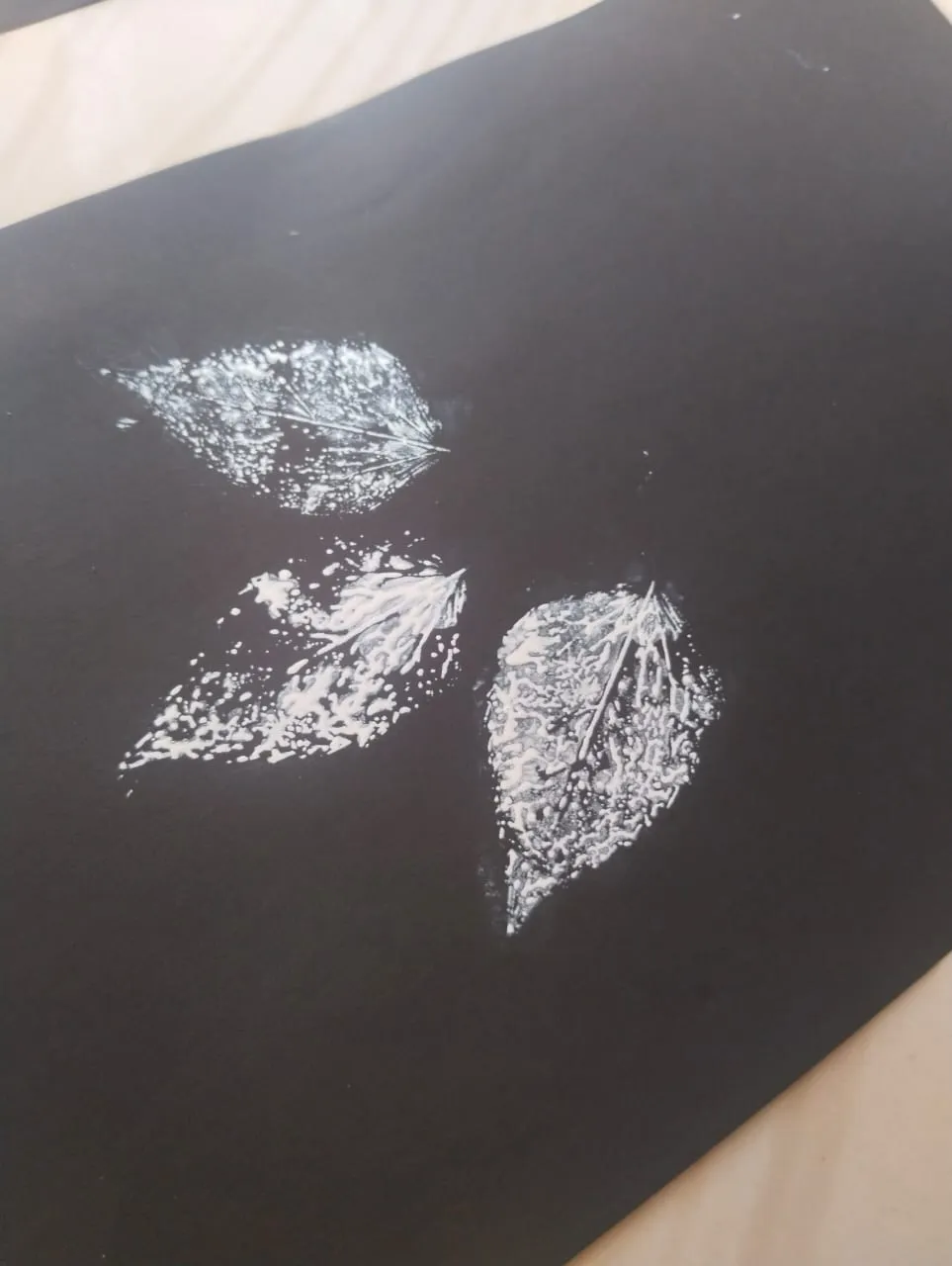

The fellows in Hemmadi participated in a mapping exercise, identifying key locations based on their daily lives, such as schools, playgrounds, milk cooperative, bus stand and health centers. This exercise helped them visualize their village from a personal perspective, linking geography with lived experiences. Meanwhile, in Keradi, fellows explored herbarium printmaking, collecting and documenting medicinal plants while learning about their cultural and health-related uses.

We had a focused session on ‘Creative documentation and Oral Histories’ in Hemmadi Library. Fellows from Keradi commuted to the library to particpate in the session. The session began with a round of introductions. In the first activity the fellows engaged in a close reading of excerpts from a short story by Suvarna Chellur. They were encouraged to notice small details, discuss their observations, and reflect on the voice behind the words. This exercise helped them engage critically with the text and appreciate different storytelling techniques. After a short break, the session resumed with a family tree-making activity, where fellows mapped out their family connections, learning to organize and visually represent relationships through guided discussions.

Oral history interviews encouraged them to record local traditions, festivals, and medicinal plant usage through storytelling with elders.

Fellowship Outcomes

- Herbarium Prints: Fellows documented medicinal plants through painting and printmaking, capturing local botanical knowledge along with written text about the plant and it use use in the region.

- Daiva Stories: Oral histories around Daiva traditions and rituals were written and Bhootas such as Bobbarya and Panjurli.

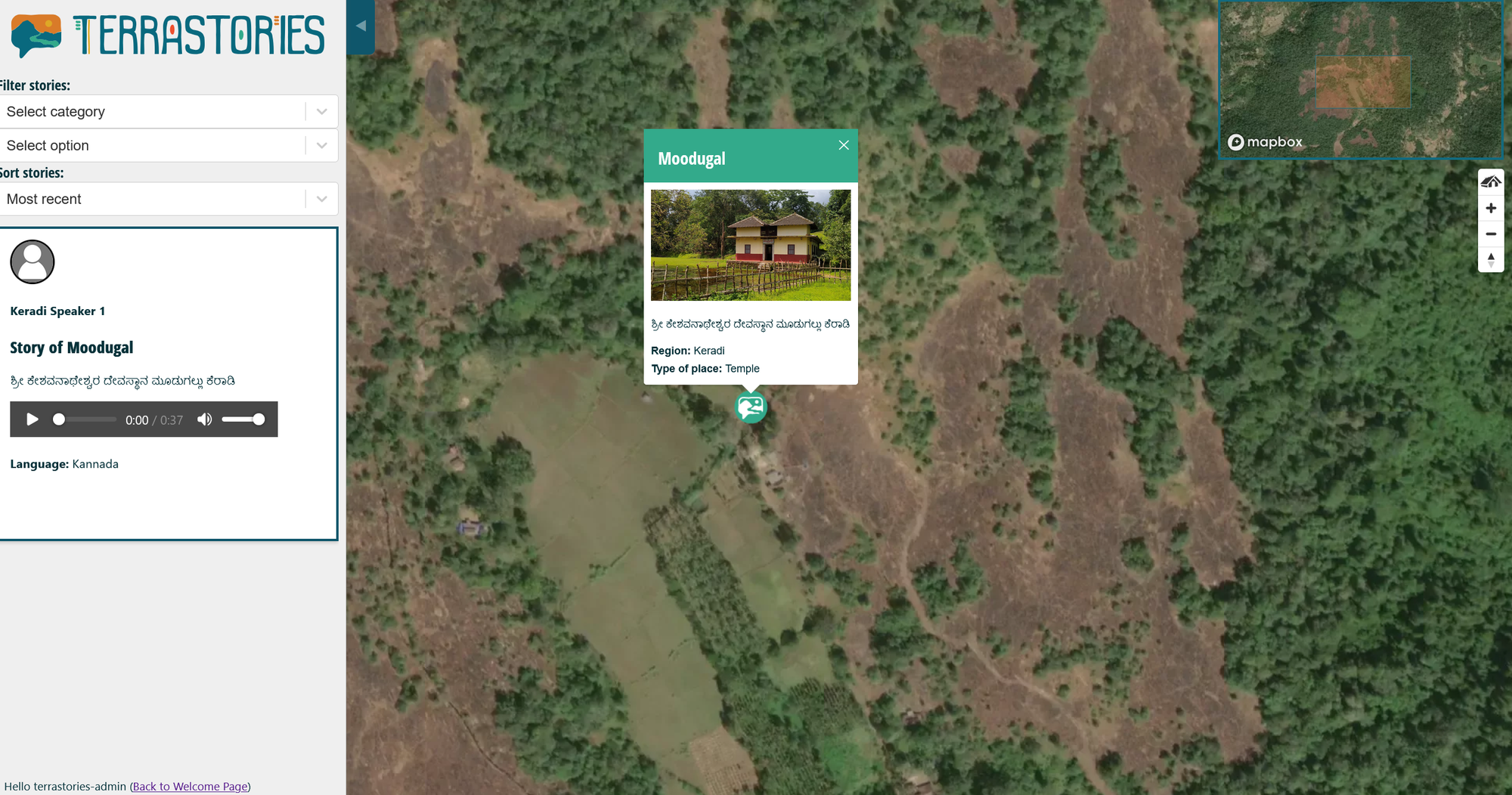

- History of the Village: Fellows mapped and documented significant places based on the stories they heard. Fellows from Keradi documented about Moodugal temple and Maranakatte temple. Fellows from Hemmadi documented how 3 religious places church, temple and mosques co exist in their village.

Exhibiting

Deiva Stories written by the children were recorded and put on a map

Reflection and Way Forward

Learning from the Place

The initial challenge of not finding youth fellows pushed us to pause and reflect. Migration is a significant factor in Kundapura Taluk. Many young people leave for work or study, shaping both the demographics and daily life in the region. Our early thoughts about time availability, willingness to participate, and local connectivity had to be re-evaluated. Through our household reviews and observatory work, we were reminded that research cannot precede the rhythm of the place, it must also listen to it. Shifting the fellowship to focus on adolescents allowed us to stay grounded, working within the realities of availability, curiosity, and local support.

What the co-design taught us

The mentors’ contributions were both logistical and thematic. Their suggestions like documenting herbs, retelling Daiva stories, or tracing the origins of village names, re-centered what counts as valuable knowledge. The fellowship became a platform for drawing together the informal and the everyday, as a way of heritage, as way of memory and nostalgia, and as a way of living systems of understanding health, community, and history. These themes also helped us move beyond categories like curriculum or skill-building, we started to focus instead on rhythm, repetition, seasonality, and the intergenerational.

What does place-based mean in migration contexts?

This experience opened up larger questions about how place-based learning must account for out-migration, especially in regions where aspirations pull youth away. We learned that being from a place doesn’t always mean being in the place. This brings up a foundation questions for our future collaborative work: How might fellowships and learning models sustain engagement when place and people are continually in flux? Can documentation practices travel with those who migrate, becoming portable acts of memory and reflection?

We see this fellowship not as an one-time intervention, but as the beginning of a longer-term engagement with place, memory, and everyday knowledge. Our hope is to continue working with the adolescents, youth, and mentors, supporting evolving forms of local enquiry, season after season, story after story. Over time, we imagine this to grow into a network of youth-led documentation practices that stay close to home and speak across regions. The process will remain open-ended, shaped by what the place invites.