Mapping Open Natural Ecosystems in Bidar - Kalyana Karnataka Karwaan

Open Natural Ecosystems (ONEs) are madeup of grasslands and scrublands that are continued to be classified as 'waste' lands. These ecosystems are beautifully and intricately tied to the health of the ecology, fauna, water and the soil of the region. These ecosystems are also linked to farming and pastoralist livelihoods & practices. The Bidar district, part of the Deccan Plateau, hosts many patches of ONEs. The Second edition of Kalyana Karnataka Karwaan had us mapping various components of ONE in three regions within Bidar district on Open Street Map as a way to understand the diverse ecologies of Hyderabad Karnataka.

For this we had to revisit Open Natural Ecosystems within the continuum of the urban – pastoral – rural – development landscape of the Bidar District, covered in our on-going long-term engagement of Climate Resource Centre. Our key focus was on introducing to the participants - What are the components of an Open Natural Ecosystem in the specific context of Bidar. How do they look like? For we are engaged in mapping this solely from satellite imagery.

Most participants had never been to Bidar, so how do they understand the kinds of ONEs that are present solely from satellite imagery? This necessitated the making of a Visual Glossary that communicated the kind, presence and locations of these components from photographs from the field along with contextual descriptions from our field engagement by us (Harshawardhan Rathod, Adhavan Sivaraj and Shreyas Srivatsa).

Visual Glossary of Open Natural Ecosystems

This is a draft of the visual glossary, a developed version will be published soon and will become a reference guide for future editions of the Karwaan

Water and Hydrology →

- Rain-fed rivers, tributaries and streams: Natural watercourses that rely on monsoon rainfall rather than perennial springs or glacial melt. The flow in the rivers, tributaries and streams vary seasonally and annually based on the variation in rainfall.

- Seasonal/ephemeral streams: These are smaller drainage channels that only carry water during and shortly after rainfall events. They're critical for local hydrology as they channel water into larger streams and tanks. During the dry season, they appear as dry beds or vegetated depressions.

- Tanks, lakes, and check-dams: Tanks (locally called keres) are traditional earthen embankments built across natural drainage lines to harvest rainwater. Check-dams are smaller structures built across streams to slow water flow and promote groundwater recharge.

- Excavated farm ponds: These are small, artificially dug water storage structures within individual farm holdings. The edges of the farm ponds can keep changing and their depth and seepage vary based on the soil type.

- Wetlands and marshy patches: These are areas with seasonally or permanently waterlogged soils that support wetland vegetation. They're most prominent during and after the monsoon, shrinking considerably during summer months. These patches provide important habitat for waterbirds, amphibians, and aquatic plants.

- Riparian buffers and gallery vegetation: These are vegetated strips along the banks of rivers, streams, and tanks. Natural riparian vegetation typically includes moisture-loving species that differ from the surrounding dry deciduous or scrub vegetation.

- Springs/seeps and waterlogged soils: Springs and seeps occur where groundwater naturally emerges at the surface, often along hillslopes or at the contact between permeable and impermeable rock layers. Waterlogged soils occur in low-lying areas where drainage is impeded, often associated with clayey substrata. These features create important micro-habitats and can be vital dry-season water sources for wildlife and livestock.

- Percolation tanks and recharge structures: Purpose-built structures in upper catchments designed specifically for groundwater recharge rather than irrigation storage.

- Step wells, Karez and historic water structures: Traditional baolis and stepped wells that may still hold water seasonally and support unique microhabitats in their shaded, moist interiors.

- Subsurface drainage patterns in laterite: The laterite geology creates distinctive subsurface water movement patterns, with water percolating through the porous upper layer and moving laterally above impermeable clay layers, sometimes emerging as seeps in the downslope.

- Tank interconnections and cascade systems: The traditional system of tanks arranged in series, where overflow from upper tanks feeds lower ones, creating a cascading water management network across the landscape.

- Breached tank embankments: Failed or deliberately breached bunds that alter downstream hydrology and create new drainage patterns, often with associated erosion features.

- Artificial drainage channels: Constructed drains, often along roadsides or field boundaries, that alter natural water flow patterns and may impact wetland formation and groundwater recharge.

- Cattle ponds and community water points: Shallow excavations or natural depressions used for livestock watering, which may support seasonal wetland vegetation and aquatic life.

- Monsoon detention basins: Natural or semi-natural depressions that temporarily hold large volumes of water during intense rainfall events, helping to reduce downstream flooding and erosion.

- Rock pools on laterite surfaces: Shallow depressions in exposed rock that fill during monsoons and support ephemeral aquatic ecosystems with specialised invertebrates and amphibians adapted to temporary water bodies.

- Groundwater discharge zones: Areas where the water table intersects the surface, creating permanently or seasonally moist patches that support distinctive vegetation communities even during dry periods.

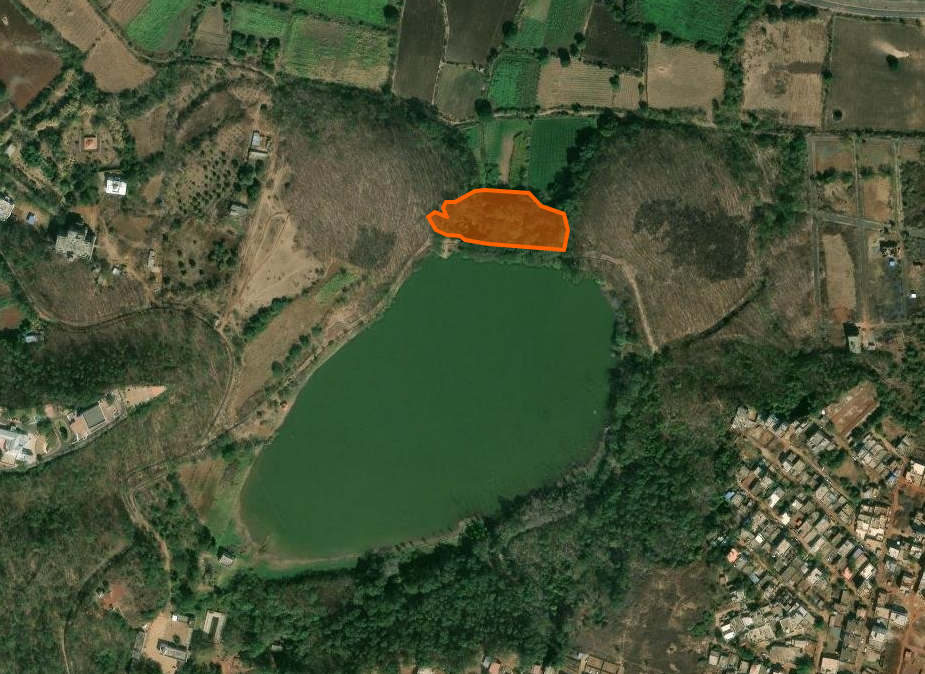

Arrival of migratory birds at Papnash lake from the months of October to February, Bidar city

Kaaranja Backwaters near Sangolgi village, Bidar South. The pond visible on the satellite image is aquaculture.

Mailar theppe Kund, Mailar temple complex, Khanapur village, Bhalki, Bidar. Kunds are used for different cultural rituals.

Grasslandlands and Open Scrub →

- Native grassland patches: These are remnant patches of indigenous grassland vegetation that have persisted despite agricultural expansion.They harbour native grass species adapted to the Deccan plateau's semi-arid climate and seasonal rainfall patterns. These patches are increasingly fragmented but serve as critical habitat for grassland birds, pollinators, and small mammals.

- Open scrub and thorn savanna: This is a mixed vegetation structure with scattered thorny shrubs and small trees interspersed with grasses. These formations occur on degraded forest lands, commons, or transitional zones between agricultural areas and natural habitats.

- Uncultivated fields reverting to grass/shrub: These are agricultural fields that have been left uncultivated and are undergoing natural succession.

- Roadside and bund-top grass strips: These are narrow linear features of grassland vegetation along roads, canals, and agricultural field boundaries (bunds). Though small in area, they're ecologically significant as connectivity corridors for pollinators, small fauna, and plant dispersal.

- Rocky grassland transitions: Grassland vegetation growing in shallow soils on or adjacent to laterite outcrops, supporting specialised drought-adapted species and creating habitat heterogeneity.

- Inter-field scrub patches: Small pockets of scrubby vegetation that persist between cultivated fields, often in areas too rocky, steep, or waterlogged to plough, serving as biodiversity refugia within intensive agricultural landscapes.

- Bund-top scrub lines: Woody shrubs growing along elevated field boundaries that are too narrow to cultivate, creating linear scrub habitat corridors through the agricultural mosaics.

Open Scrub area Chatnall, Aurad, Bidar

Panorama view of Bellura grassland, Bidar.

Grassland near Dhanura thanda

Tree cover other than in forests →

- Scattered trees and windbreaks: These are individual trees or small groups planted or retained within agricultural landscapes, often serving as windbreaks to protect crops and soil.

- Agroforestry rows, orchard blocks: These are deliberately planted tree systems integrated with agricultural production. Orchard blocks are dedicated plots of fruit trees such as mango, guava, or pomegranate that have become increasingly popular as farmers diversify from rainfed cereals.

- Avenue trees along roads and canals: These are linear plantings of trees along transportation and irrigation infrastructure. Though often consisting of introduced species, these linear features create important wildlife corridors connecting fragmented habitats across the agricultural landscape.

- Sacred groves and village woodlots: Sacred groves are patches of native vegetation protected for religious or cultural reasons, often associated with temples or shrines. Village woodlots are community-managed tree plantations established to meet local needs for fuel wood, fodder, and small timber.

Teakwood plantation in Grassland, BIdar

Halbarga Blackbuck Safari area, Eucalyptus tree along with native neem trees.

Halbarga Blackbuck safari. A wall of Glycerdia trees in middle of grassland.

Agricultural-natural mosaics →

- Rainfed field mosaics with natural edges: These are agricultural fields dependent on monsoon rainfall that retain strips of natural vegetation along their boundaries. The natural edges—often containing native grasses, shrubs, and scattered trees—create important transition zones between cultivated and uncultivated lands.

- Field bunds with vegetation: Field bunds are the raised earthen boundaries between agricultural plots, essential for water management and soil conservation in undulating terrain.

- Fallow–crop rotational patterns: This refers to the temporal pattern of leaving fields uncultivated for one or more seasons as part of the farming cycle.

- Live hedgerows and boundary shrubs: During fallow periods, fields undergo natural succession with colonisation by native and fast growing grasses grasses and herbs, creating temporary grassland-like habitats.

Rocky outcrops and lateritic plateaus →

- Exposed rock sheets and pavements

- Laterite caps and escarpments

- Boulder fields and tors

Basalt rocky outcrop Bidar grassland Rakshyal Grassland

Lateritic area present in Bellura Grassland, Bidar

Grassland area near Amdabad cross, Nittur, Bhalki, Bidar

Soil and erosion patches →

- Eroded (Natural) gullies and rills: These are linear erosion features formed by concentrated water flow during monsoon rains. Rills are small shallow channels, whilst gullies are larger, more permanent channels that can be several metres deep.

- Extreme erosion patches: These are severely degraded areas characterised by deeply dissected terrain with numerous gullies, sharp ridges, and minimal vegetation cover.

- Sediment plumes into tanks: These are visible patterns of muddy, sediment-laden water entering tanks (reservoirs) and other water bodies, most apparent during and immediately after monsoon rains.

Commons and grazing grounds →

- Village commons/“gomal” lands: These are community-owned lands traditionally used for collective grazing, fodder collection, and other village activities. These areas typically contain a mixture of native grasses, scattered shrubs, and occasional trees.

- Open grazing corridors: These are linear pathways used by livestock to move between villages, grazing grounds, and water sources. Traditionally, these corridors were well-defined features of the landscape, but many have been narrowed or blocked by agricultural expansion and infrastructure development.

- Seasonal camping or penning sites: These are locations where herders temporarily keep livestock, particularly during the dry season when animals are moved to areas with available grazing and water.

Grazing ground Sindol thanda

Commons Dhanura thanda

Linear natural features →

- Canal and distributary banks with vegetation: These are the vegetated edges along irrigation canals and their smaller distributary channels.The banks of these canals often support linear strips of vegetation—grasses, herbs, and sometimes shrubs or small trees—that benefit from the proximity to water.

- Drainage lines and Hallahs: Hallahs are natural drainage channels that carry water during the monsoon season, ranging from small seasonal streams to larger watercourses. During the dry season, many hallahs remain dry but retain strips of vegetation in their beds and along their banks where soil moisture persists longer.

- Greenways along high-tension lines or rail: These are linear strips of vegetation that develop along infrastructure corridors such as electricity transmission lines and railway tracks. The vegetation in these strips often consists of native grasses, shrubs, and sometimes trees (kept below certain heights near power lines), creating continuous habitat strips that can extend for many kilometers.

Grassland with agriculture land near Honnekeri village.

Wet dry ecotones →

- Tank drawdown zones: These are the transitional areas around tanks (traditional water harvesting structures) that are alternately submerged and exposed as water levels fluctuate seasonally. During the monsoon, these areas are under water, but as the dry season progresses and water is used for irrigation or evaporates, concentric bands of vegetation are revealed.

- Monsoon grass swales: These are shallow, elongated depressions in the landscape that channel water during the monsoon season and support lush grass growth. During the monsoon, these swales hold water temporarily and support vigorous growth of moisture-loving grasses and sedges. As the dry season advances, the surface water disappears, but the swales retain soil moisture longer than surrounding areas, allowing their vegetation to remain green for extended periods.

- Seasonal wet grasslands: These are low-lying areas that become waterlogged during the monsoon and transform into moist grasslands, persisting into the early dry season before gradually drying out.

Painted Stork migratory birds which are seen marshy areas of water bodies.

Degraded or transitional lands →

- Scrub cleared recently: These are areas where native or semi-natural scrub vegetation has been recently removed, typically for agricultural expansion, fuelwood collection, reforestation or land development. Recently cleared sites are identifiable through exposed soil, cut stumps, and the absence of mature vegetation. These areas are ecologically significant because they represent habitat loss and fragmentation, but they also present restoration opportunities if intervention happens quickly.

- Gliricidia or other invasive patches: These are areas dominated by invasive 'exotic' species, particularly Gliricidia, introduced for fuelwood and fodder that has spread aggressively across commons, wastelands, and degraded forests, forming dense, impenetrable thickets that exclude native vegetation and reduce biodiversity.

- Abandoned quarry pits: These are excavation sites where laterite, stone, or other materials were extracted for construction purposes but are no longer actively mined. These sites typically feature exposed rock faces, accumulated debris, disturbed soil profiles, and often temporary or permanent water accumulation in pit bottoms.

- Dumping grounds and waste accumulation sites: Areas used for disposing of agricultural waste, construction debris, or household refuse, which alter soil chemistry and vegetation

- Fire-affected scrublands: Areas subjected to repeated burning for management or clearing, leading to shifts in vegetation composition towards fire-adapted species and loss of fire-sensitive native plants—the frequency and intensity of burning determines degradation severity.

- Degraded tank beds: Tanks that have been abandoned or whose catchments have degraded, leading to siltation, vegetation encroachment in former water areas, and loss of storage capacity.

Grassland in conversin to mining land, Bellura, Bidar

Basalt Mining area now turned into water body halbarga grassland area

Cultural ecological nodes →

- Sacred tanks and kalyanis: These are water bodies with religious and cultural significance, often associated with temples, mosques, dargahs or historic sites.

- Sacred groves and temple hills: These are patches of vegetation protected due to religious beliefs and cultural taboos against cutting trees or disturbing wildlife within them.

- Community-managed plantation edges that function as habitat: These are planted tree areas—such as community woodlots, social forestry plantations, or farm forestry boundaries—that, through time and appropriate management, have developed ecological value.

- Dargahs and associated vegetation: Sufi shrines (dargahs) often surrounded by mature trees—particularly neem, banyan, and khirni—that are protected due to their association with saints.

- Graveyards and burial grounds: Historic Muslim graveyards and Hindu cremation grounds typically retain trees and shrubs due to cultural restrictions on intensive land use.

- Fort area vegetation: Accumulated natural vegetation over centuries in areas not actively managed, including rock faces, ramparts, and abandoned portions. These areas support specialised plant communities adapted to built structures and provide habitat for rock-dwelling species.

- Abandoned stepwells and baolis: Historic water structures that are no longer in active use but retain water seasonally, supporting distinctive plant communities adapted to damp, shaded conditions, along with bats, swallows, and other species that use the structures for roosting or nesting.

Median points found in grasslands of Bidar.

Footprints of user found in grassland. Chatnall, Bidar

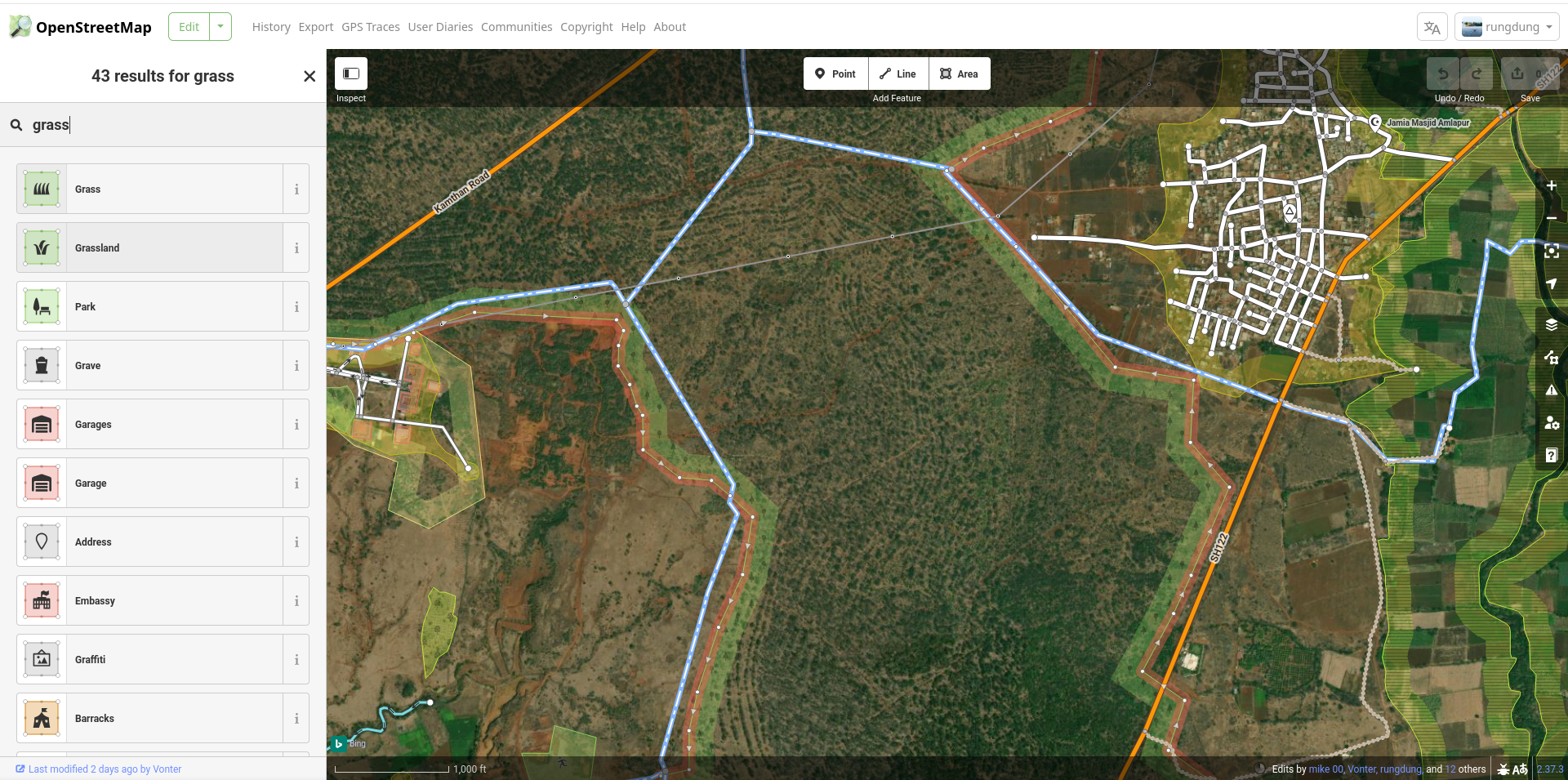

Getting used to the editor

The OpenStreetMap editor was convenient and easy for new editors to get used to. You only have to be comfortable moving around and drawing with a mouse. Once people were comfortable, we quickly got around to mapping farmlands, grasslands, planted forests, water bodies and wetlands.

Soon after we would often run into questions of what is this really? Its a bunch of trees, I don’t know what kind, but it is definitely a micro habitat in the ecotone between a lake and fields for example. How does one identify it as one thing? It is multiple things. It is evident that not everything may be categorisable in that sense, and it is also not our ambition to do so. Going down that slope would mean we would be attempting to make a copy of that world (The map is not the territory!) to really represent it on the map.

So how do we map what may not match the global definition of a grassland or wetland? That became one of the defining conversations of the day, as we realised that we will have to use our own local terms and schemas to define these regions without getting into the need to define ‘truthfully’ for ‘data’.

How do we document the seasonality of the space as well? A plot of farm may be underwater because of its proximity to a reservoir and a grassland may be grazed much more commonly than other lands due to lack of access.

There are also developments on the ground that are difficult to identify with the present resolution of satellite imagery and attempts to classify may have to be revisited constantly.

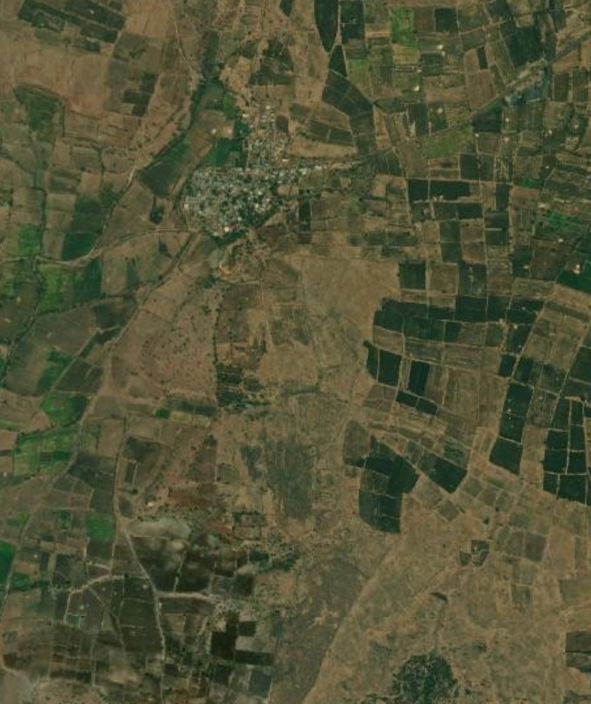

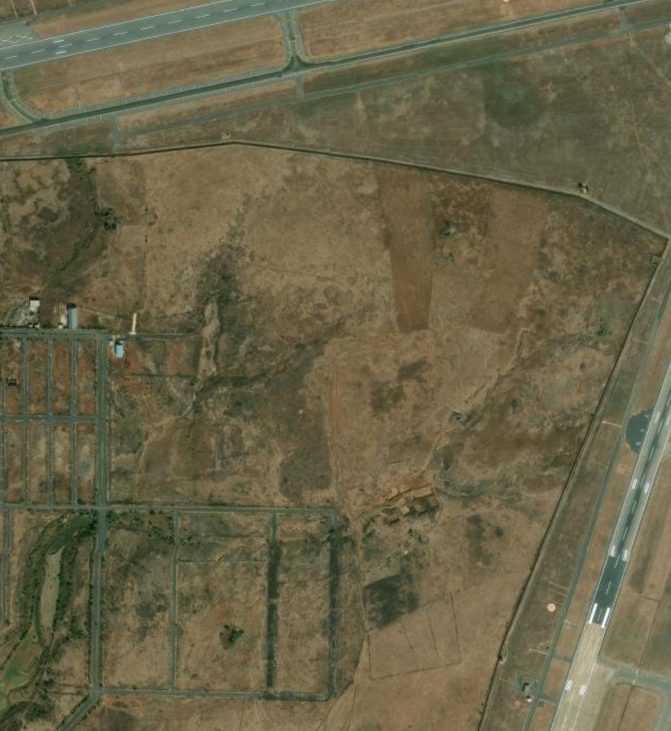

Satellite Imagery from near Sindhol Thanda and the post mapping and mining regions near the thanda

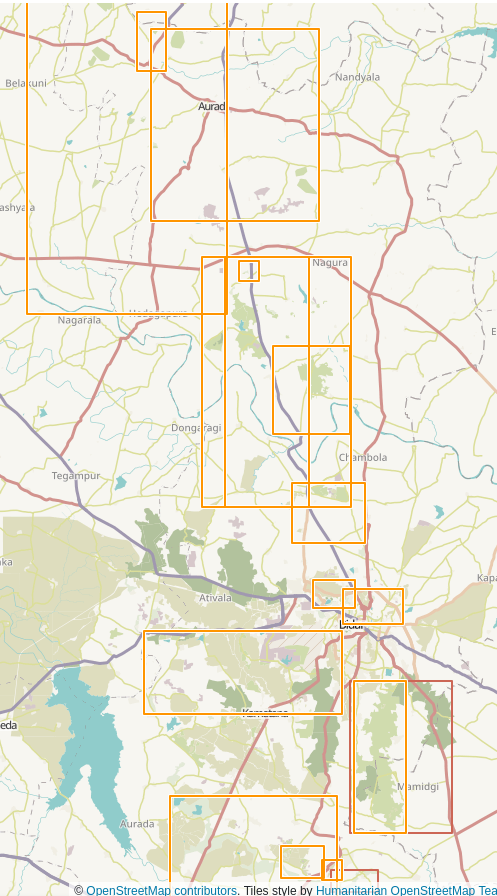

Three groups of 4 people each had mapped ONEs in Aurad Taluk, in the region above Bidar City, and in the region below Bidar City near Sindhol Thanda. Each region presented its own unique characteristics. Right next to the city, there are layouts and urban elements intersecting with shrubs, grasslands and wetlands. South of the city, but not too far away, mining is prominently present. And in Aurad, it is relatively less diverse.

On the left: Mining and Solar parks near Sindhol Thanda. On the right: Layouts and farms prominenly transitioning away from the city and the Papnash lake

By the end of the day we had mapped a large portion of Bidar and Aurad talukas. And ended the day with 38 ‘changesets’, a term used to refer to each upload that users make on OSM. We had 10 editors uploading with each group having one person who has seen or walked along these kinds of environments in Bidar.

A snippet of edits that were uploaded on the day and Areas where we were mapping. Aurad in the North to Bidar South